|

0 Comments

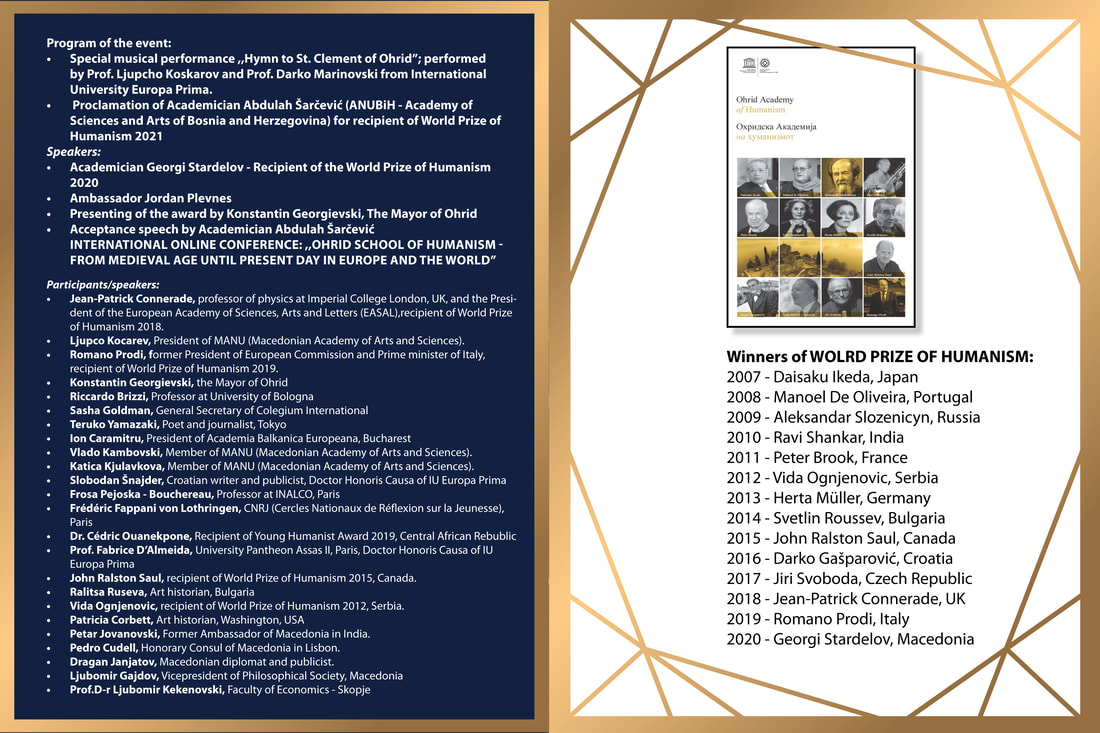

Nicolas Petrovitch Njegosh - Crown Prince of Montenegro, was born July 7, 1944 in Saint Nicolas du Pélem (Côtes d’Armor). He obtained his architectural diploma in 1971 at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris and has since worked as an independent architect. His professional experience has spanned several directions: Self-construction, urban environment, town planning, construction of industrial and agricultural buildings, renovation of administrative and commercial buildings. After 70 years of exile from the Petrovich Njegosh family, following the annexation of Montenegro to Serbia, he returned to Montenegro on the occasion of the repatriation of the bodies of King Nikola, Queen Milena and Princesses Vijera and Ksenija the October 1, 1989. Inspired by this event and shortly after, the fall of the Berlin Wall, he created and directed the Biennale of Contemporary Art in Cetinje, the royal capital of Montenegro from 1991 to 2002. These reunions with Montenegro allowed him to renew contacts with several members of European royal families, some of whom were linked by marriage to the Petrovich Njegosh family. From the start of the Yugoslav conflict, he launched an appeal for peace following the first bombing of Dubrovnik and called on the Montenegrins not to participate in the conflict. During the period of the conflict, he created and chaired the IZBOR association (legal defense of victims of ethnic discrimination in the former Yugoslavia). He also created and chairs the SEM association (Solidarity Europe Montenegro) which organizes several humanitarian aid campaigns in Montenegro. Since 2002, he has organized with the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts (Paris la Seine) several architecture and town planning workshops in the village of Gornja Lastva, in Montenegro. Five years after the regained independence of Montenegro, in July 2011, the Parliament of Montenegro passed a Law on the status of the heirs of the dynasty, which included the creation of a Petrovich Njegosh Family Foundation. The Foundation of which he is President has a triple field of action: Solidarity, Environment and Cultural Heritage. Since 2012 the Foundation has initiated, supported and accompanied more than 200 projects in these different sectors in Montenegro. On April 21, 2017, he was decorated in Paris, at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, with the rank of Knight of the Legion of Honor by Madame Florence MANGIN Director of Continental Europe. Letter of acceptance of World Prize for Humanism 2024Winner of the World Prize for Humanism for 2023, with which the Ohrid Academy of Humanism celebrates the name of St. Clement of all world meridians, is Victor Friedman, a world-renowned linguist, Slavist and Macedonist, professor at the University of Chicago, USA.

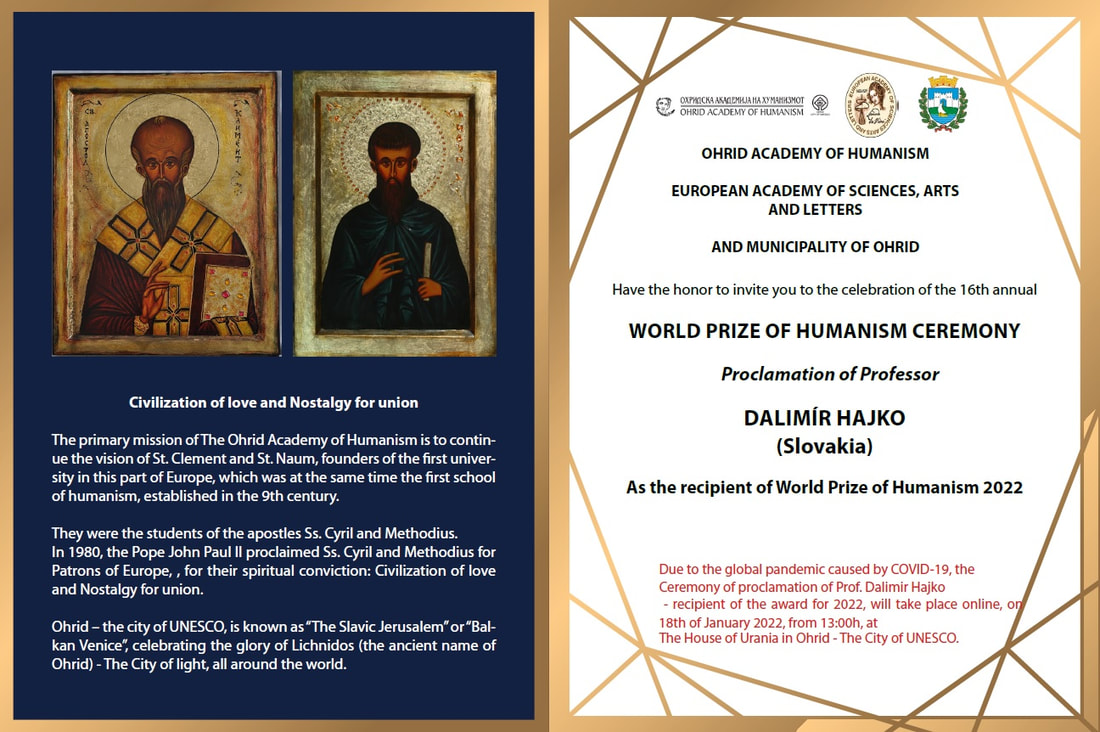

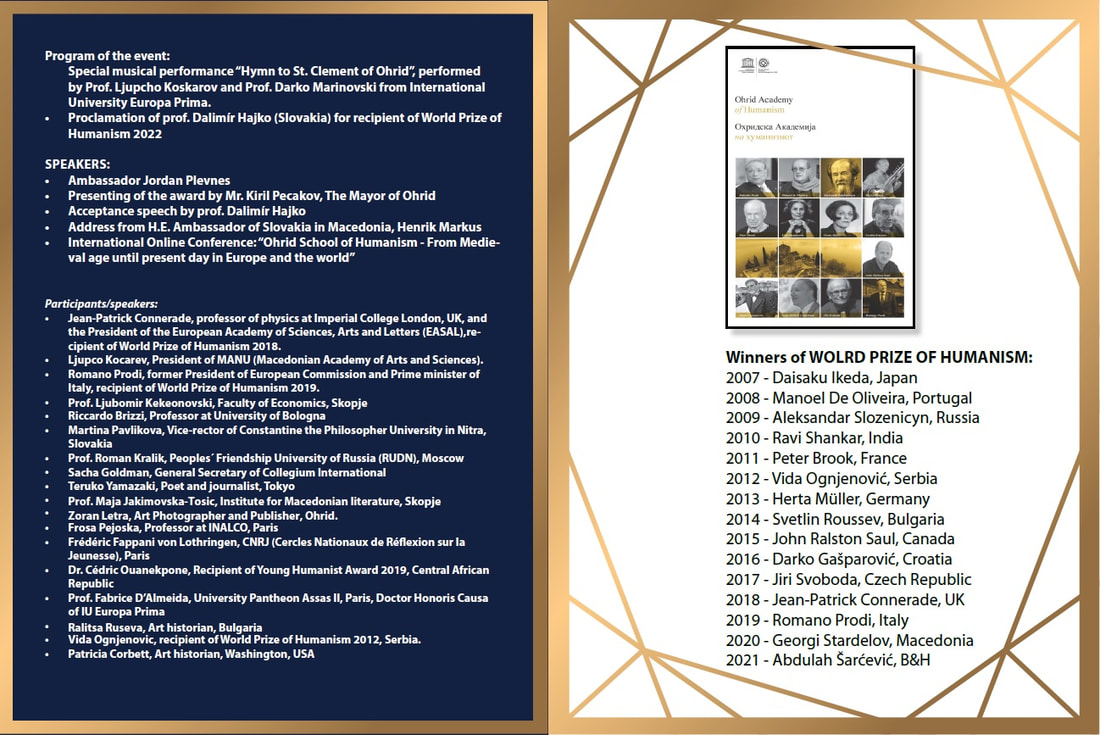

Professor Friedman is the seventeenth winner in a row of this exceptional recognition with which Ohrid, the UNESCO city, has already crowned Nobel laureates Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, Herta Müller, world legends Daisaku Ikeda, Ravi Shankar, Peter Brook, Manoel De Oliveira, Romano Prodi, awakening the sources of spiritual memory from the first medieval school of humanism, founded by the students of St. Cyril and Methodius, the protectors of Europe. The award ceremony will be held on August 9, 2023, on the "Summer St. Clement", because at the same time on that day, the Memorial-landmark on the Dolna porta square in Ohrid, whose artistic founders are the Bulgarian painter Svetlin Russev and the Macedonian sculptor Zharko Basheski, will be ceremonially unveiled. With that memorial, on which all previous winners of the World Prize for Humanism will be recorded, the ancient Ohrid and its millennial history will be declared in European memory as the Center of World Humanism. Mayor Kiril Pecakov will present the prize to the winner Friedman, and then after the speech by Ambassador Plevnes about the exceptional scientific and humanistic work of Friedman, the laureate will deliver his solemn acceptance speech. At the ceremony, to which all previous winners will be invited, in the presence of a larger international assembly of guests, including representatives and mayors from Ohrid's sister cities from Europe and the cities under the auspices of UNESCO, Romano Prodi, former President, will give appropriate speeches of the European Commission and winner of this prize, Jean-Patrick Connerade, from Imperial College London, President of the European Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, and German Nobel Laureate Herta Müller. The ceremony is expected to be attended by the General Director of UNESCO, Audre Azoulay, as well as presidents of international cultural and educational foundations from Europe and the world. The councilors of the Municipality of Ohrid proposed that the international act of declaring Ohrid as the Center of World Humanism should be marked with a "Path of Humanism" that will lead from the Dolna Porta to St. Sofia and on which the names of the recipients of the Prize for Humanism will be placed. Paradoxes of Humanism - Dalimír Hajko There are few words in the vocabulary of modern culture that are as abused as humanism. In the name of humanism, the civilizational backgrounds of countries change violently, in the name of humanism, religions are attacked - because they do not suit the ideas of the attacker. Humanism is a paradox in its very essence. For an individual to become a true humanist, he must deny himself and focus on his surroundings, on other people, and on other beings. In a sense, even on inanimate nature. He does not prefer humanity in himself, but in relation to others. Mankind has survived a century of catastrophic proportions, experienced defeats of good, achievements of evil. Who has the right to speak of humanism as a worldview, of humanity as a positive passion? Humanism can also act in a way as a narcotic or even madness. He wants to drown out the impending catastrophe and build futurological illusions. But at the same time it brings a person back to himself. In an abstract philosophical projection, it is an anthropological constant. Humanism is as simple as it is mysterious. There is nothing simpler than "loving humanity" and nothing more complicated than loving a particular person - a part of this humanity - often groping, betrayed and abandoned by all people. The nobility and pervasiveness of the idea of humanism is reflected in the ability to kiss a leper. But it is also certain that we should not try to enter the lives of others against their will. Our time is influenced by the general insignificance attributed to the individual. It is suppressed by an explosive social dynamic, which transposes the ideas of humanism in the life of the individual with his needs, passions and loves into the position of abstract pacifism, which, however, often acquires a militant dimension. The idea of humanism is often oversaturated with spiritual pride. "I am a humanist, who is more"? Not spiritual pride, but spiritual vanity. Cruel humour. Humanism is a process of purification. It must not be filled with hatred for life, it must not be saturated with fear, especially not with fear of the world. Indeed, the world is cruel and inhuman, and we are always tempted to succumb to bigoted, dark and fanatical ideas. The patience of vice is infinite. At the same time, we often think that we are doing the right thing, even that we are doing good. We lack the idea of faith that would strictly define the boundaries of our lives. And their power lines do not run in the direction of our egoism, but also in the direction of our ignorance. Let us be silent if we cannot assess the situation comprehensively and impartially. Then we do evil - and regret it. There is another paradox: Humanism is also a revelation of the mystery of sin. For he who believes in humanism necessarily presupposes the possibility of the existence of its opposite - antihumanism. How should a humanist treat a bearer of anti-human beliefs? Should he suppress, destroy, re-educate him? But who would be the arbitrator of our action here? Humanism is not a self-serving product of our convictions. Its principles are not determined by anyone. One of the heroes of Graham Green's novel The Heart of the Matter, reminiscent of a small provincial town, says, "Here one can love the human being as God loves it, who knows the worst about it." The criteria of sin and its borders are different for individuals as well as for social groups, religious conglomerations, civilization triads. We should not confuse humanism with compassion or altruism, with charity. This is not to say that it is more than the virtues mentioned. It is neither more nor less, it is different. It grows out of a paradox and lives a paradox. Its main message is to overcome the paradox, but the main paradox is to realize the impossibility of such a procedure. We often imagine humanism as a series of deeds, ideas, concepts or relationships between which one is intertwined without identifying with them as a whole. The essence of the paradox is that we identify with some without problems, with others after discussion, and some we reject. However, the question is whether any whole exists at all. Whether the holistic perception of humanism is legitimate and correct. Can we call any actions of a person who has previously committed evil an act of humanism? Is it even possible to think about humanism at all in the relation to good and evil? And to create a coherent idea of humanistic action? What seems bona fide to some as a humane act of good, others may perceive as inhuman evil. This is clearly reflected in the field of politics. The policy of forcibly exercising power convinces us of this, so to speak, on a daily basis. Every politician wants good for others. At least he claims it and maybe he believes it. These questions are notoriously known: What is the success of humanism? Is it humane to enjoy the achievements of civilization when millions are starving? Is it humane to destroy the moral foundations of civilizations because, from our point of view, they are inhumane? And - let me have a heretical idea - is it humane to protect predatory animals when we cannot protect the weak and helpless? And ultimately – is fury humane at all in the substantive meaning sense of the term? Who decides whether it is humane to fight against something that, in our view, seems inhumane? Is it humane to repress people with a different belief when we cannot fully accept our own? Instrumented political practice on a daily basis shows the bizarre consequences of the progress of the social sciences, which are accompanied by abstractions such as universal human rights, pluralism and democracy. The fight for peace is sometimes more precious to us than a peaceful life in peace. Life, not death. "For me, every contempt of death is ridiculous," Saint Exupéry wrote. "If it is not rooted in the responsibility we have taken on, it is only a sign of mental illness or a fad of youth." But responsibility requires constant truths. Who knows whether the dogmatists we so often rebel against in the name of progress and necessary change are at least partially right when they convince us of the need to believe in constant truths. Life is born from life, image from image, feeling from feeling. What is humanism born from? There is only one premise for humanism: it is the goal of action. It is like in the art of archery, which the philosophy of Zen Buddhism teaches us: the trajectory of the bullet is not primarily important, the goal it is aimed at is paramount. If the shot of our action is guided by the idea of the final image of the human state, then it also circumvents our weaknesses, hesitations, uncertainties, many twists and turns - it has a picture of the future ahead of it. In the name of this goal, it acts as a substantial anticipation of this future. However, the paradox of the goal lies in the fact that the symptoms of the coming transformations are invisible and insensitive, that the individual as well as society is confronted with them only afterwards and with a considerable delay. Therefore, they are often ineffective and misunderstood. People who are old, sceptical, and therefore wise, they know, they have had time to acquire this knowledge; people of everyday practice longing for quick success will only understand this in the future. Humanism cannot be fixed on static values - it is born from the movement of the mind - it is dynamic because it responds to a problem in the coordinates of permanent change, but seeks stability in these changes. The image of the search for permanence in change allows us to better realize the hidden dimensions of life. We have to deal with our limitations and abilities. Approach the world together with other pilgrims in this valley of decision. There are different styles of archery and different types of bows. Each requires a different force applied to each part of the archer's body so that the arrow reaches the target accurately and infallibly. Concentrating on the target requires the person to be in line with the arc of the bow, to feel the path of the arrow, and thus achieve the accuracy of the hit, find peace in motion, immobility in speed. In other words, each situation requires a different weapon, a different solution, a different way to reach the goal. Humanism is the path of a pilgrim seeking truth in a sea of untruth, reality in the unreal, light in the dark. But to see, we must first understand darkness, its significance for the concentration of our energy. If we want to achieve a sense of inner peace, we should unravel the mystery of unrest, understand the essence of the insecurity that surrounds us in today's hectic times. Because none of us is an abstract personality, we must intuitively feel a concrete, full presence. It is the ability to accept the circumstances of our lives. Presence calls us to actions that lead to the essence of humanity. The only salvation for humanism is to encourage people to be more sensitive to the problems of their companions. Each of our thoughts on life and creation should give us above all the courage, the courage to live and create, the courage of new beginnings. And even when our work is perhaps beyond the zenith. This courage is our freedom. It survives untouched even in times of adversity, in times of moral uncertainty and political volatility. Our freedom is the opportunity to start at any age, to always revive our intentions and actions, to always re-shape and reform relationships, to always re-create things that are beautiful, great and good. Unless the power of this courage ceases to work in us, the power of possibility, the power of new initiative, we are free, we are the freest of beings, because we have received a gift, the greatest of gifts. The possibility of freedom is our power, which is often hidden, almost unknowable, intangible. But if it can proceed from his privacy and become a public, in the best sense profaned word political force, it can also form the basis for public, political freedom, it can define the secular, profane space of mundaneness for sacred, miraculous things. It can be useful for everyone. It is the most valuable thing a person can have and pass on to others. Парадоксите на хуманизмиот |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed